Investor Bulletin - Mutual Fund Fees and Expenses

May 12, 2014

The SEC’s Office of Investor Education and Advocacy is issuing this Investor Bulletin to explain some of the most common mutual fund fees and expenses. As a general introduction to mutual fund fees and expenses, this Investor Bulletin does not identify all of the fees that you may pay to buy and own shares in a mutual fund. This Investor Bulletin will, however, familiarize you with some typical mutual fund fees and expenses and show you how those fees and expenses reduce the value of your fund’s investment return.

As with any business, it costs money to run a mutual fund. There are certain costs associated with an investor’s transactions (such as buying, selling, or exchanging mutual fund shares), which are commonly known as “shareholder fees,” and ongoing fund operating costs (such as investment advisory fees for managing the fund’s holdings, and marketing and distribution expenses, as well as custodial, transfer agency, legal, accounting, and other administrative expenses). Although these fees and expenses may not be listed individually as specific line items on your account statement, they can have a substantial impact on your investment over time.

The Impact of Mutual Fund Fees and Expenses on Your Investment Portfolio

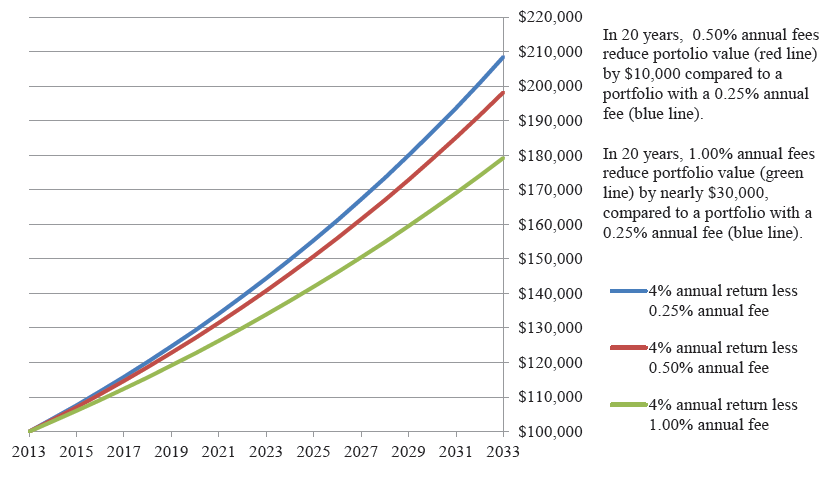

Fees and expenses vary from fund to fund and the amount you pay may depend on the fund's investment strategy. A fund with high costs must perform better than a low-cost fund to generate the same returns for you. Even small differences in fees from one fund to another can add up to substantial differences in your investment returns over time, as the graph below shows.

Portfolio Value From Investing $100,000 Over 20 Years

The graph above shows how mutual fund fees and expenses can affect your mutual fund investment portfolio. The graph illustrates the effect of fees and expenses in three hypothetical scenarios, as represented by the blue, red, and green lines.

- The blue line represents the investment portfolio of a hypothetical mutual fund that does not charge shareholder fees and that produced a 4% annual return over 20 years and had annual operating expenses of 0.25% (i.e., $25 for every $10,000 invested) during that period. If you invested $100,000 in this fund, then after 20 years your investment portfolio would be worth approximately $208,000.

- The red line represents the investment portfolio of a hypothetical mutual fund that does not charge shareholder fees and that produced a 4% return over 20 years and had annual operating expenses of 0.50% (i.e., $50 for every $10,000 invested) during that period. If you invested $100,000 in this fund, then after 20 years your investment portfolio would be worth approximately $198,000. The fees and expenses would have consumed about $10,000 more of your investment portfolio over that time, compared to the hypothetical mutual fund with annual operating expenses of 0.25%.

- The green line represents the investment portfolio of a mutual fund that does not charge shareholder fees and that produced a 4% return over 20 years and had annual operating expenses of 1.00% (i.e., $100 for every $10,000 invested) during that period. If you invested $100,000 in this fund, then after 20 years your investment portfolio would be worth approximately $179,000. The fees and expenses would have consumed nearly $30,000 more of your investment portfolio over that time, compared to the hypothetical mutual fund with annual operating expenses of 0.25%.

The more you pay in fees and expenses, the less money you will have in your investment portfolio. And these fees and expenses really add up over time. Given the compounding effect of fund fees and expenses and their impact on your investment returns, you may want to use a mutual fund cost calculator to compute how the costs of different mutual funds would add up over time.

Shareholder Fees and Annual Operating Expenses Generally

Some funds may cover the costs associated with your transactions and your account by imposing fees and charges directly on you at the time of the transactions (or periodically with respect to account fees). You can find these fees and charges listed in a standardized fee table located near the front of a fund’s prospectus, under the heading “Shareholder Fees” (described below).

In addition, funds typically pay their regular and recurring fund-wide operating expenses out of fund assets, instead of imposing these fees and charges directly on you. Because these expenses are paid out of fund assets, you are paying them indirectly. These expenses are identified in the standardized fee table in the fund’s prospectus under the heading “Annual Fund Operating Expenses” (described below).

It is important to understand that mutual funds do not impose these fees and expenses arbitrarily. Rather, the fund’s board of directors is responsible for overseeing the fund’s operations and management. The fund’s directors, and its independent directors, in particular, function as “watchdogs” who are supposed to look out for the interests of the fund’s shareholders. One of the most significant responsibilities of a fund’s board of directors is to negotiate and review the advisory contract between the fund and the investment adviser to the fund, including fees and expense ratios.

But even though these fees and expenses may be entirely appropriate based on the fund’s operations, these costs may be higher than what you might be willing to pay—so be sure to comparison shop and decide whether a similar fund with lower expenses would make better sense for you. Remember, the more you pay in fees and expenses, the less money you will have in your investment portfolio.

Before investing in a mutual fund, you should read the fund’s prospectus carefully. Some funds provide a “summary prospectus” that includes information on how you can obtain a full-length prospectus, while other funds may deliver a full-length prospectus only. If you are purchasing a mutual fund through a financial professional, ask that person to explain all the charges that may apply to your investment in the fund.

Mutual Fund Table

A mutual fund is required to disclose its shareholder fees and operating expenses in the form of a standardized fee table in its prospectus.

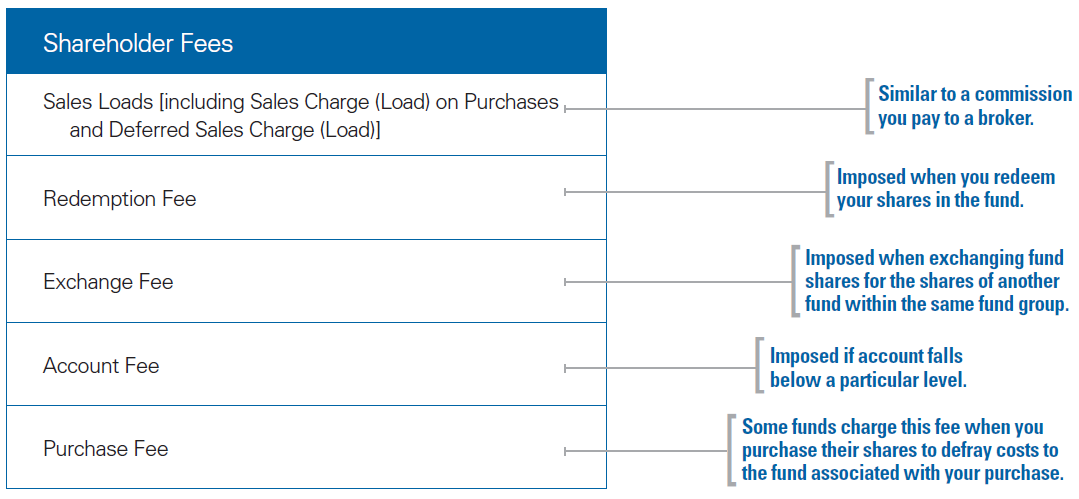

In the fee table, under the heading of “Shareholder Fees,” you will find some or all of the following items:

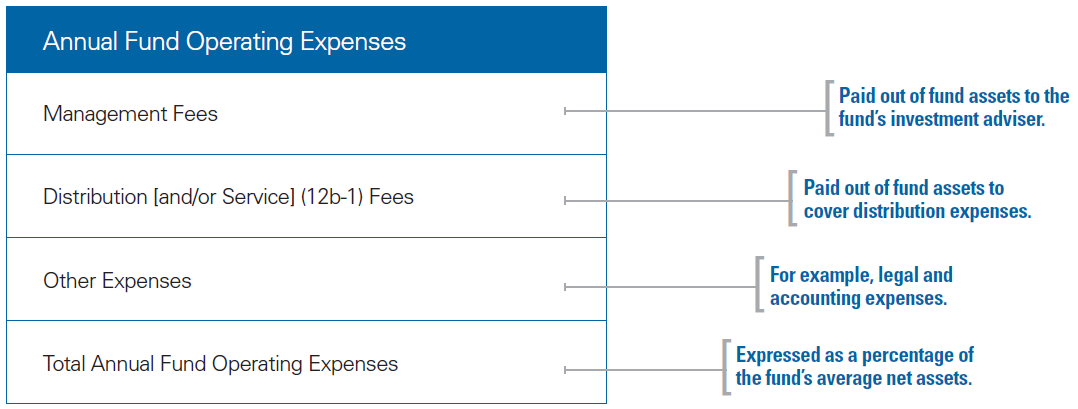

In the fee table, under the heading of “Annual Fund Operating Expenses,” you will find some or all of the following items:

Below is a discussion of shareholder fees and annual fund operating expenses. For a description of other fees and expenses associated with investing in mutual funds, see our Investor Bulletin: How Fees and Expenses Affect Your Investment Portfolio

Shareholder Fees

In this section, we discuss those items that you will find under the heading of “Shareholder Fees” in the fee table.

Sales Loads

Funds that use brokers to sell their shares compensate the brokers. Funds may do this by imposing a fee on investors, known generally as a “sales load” (or “sales charge (load)”), which is paid to the selling brokers. In this respect, a sales load is like a commission you pay when you purchase any type of security from a broker.

While the SEC does not limit the amount of sales load a fund may charge, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) does not permit mutual fund sales loads to exceed 8.5%. The percentage is lower if a fund imposes other types of charges.

There are two general types of sales loads—a front-end sales load that you pay when you purchase fund shares and a back-end or deferred sales load that you may pay when you redeem your shares. When purchasing fund shares, you may or may not have a choice of whether to pay a front-end sales load, a back-end sales load, or some other deferred sales load, depending on the fund.

Sales Charge (Load) on Purchases

The category “Sales Charge (Load) on Purchases” in the fee table includes sales loads that you might pay when you purchase fund shares (also known as “front-end sales loads”). Typically, a mutual fund calculates the amount of front-end sales load based on a percentage of the sales price. The key point to keep in mind about a front-end sales load is that it reduces—right off the top—the amount of money that you have available to purchase fund shares (as described in the example below).

For example, if you write a $10,000 check to a fund to purchase fund shares, and the fund has a 5% front-end sales load, the total amount of the sales load will be $500. The $500 sales load is deducted from your $10,000 check (and typically paid to a selling broker), and assuming there are no other front-end fees, the remaining $9,500 is used to purchase your fund shares.

Sometimes, funds offer discounts for larger investment amounts—usually called “breakpoint discounts”—in which the sales load is reduced if more than a certain amount of money is invested.

Deferred Sales Charge (Load)

The category “Deferred Sales Charge (Load)” in the fee table refers to a sales load that you might pay when you redeem fund shares (that is, sell your shares back to the fund). You may also see this referred to as a “deferred” or “back-end” sales load. When you purchase shares that have a back-end sales load instead of a front-end sales load, no sales load is deducted at the time of your purchase, so all of your money is used immediately to purchase fund shares (assuming that no other fees or charges apply at the time of purchase).

For example, if you invest $10,000 in a fund with a 5% back-end sales load, and if there are no other “purchase fees,” the entire $10,000 will be used to purchase fund shares, and the 5% sales load is not deducted until you redeem your shares, at which point the fee is deducted from the redemption proceeds.

Typically, a fund calculates the amount of a back-end sales load based on the lesser of the value of the shareholder’s initial investment or the value of the shareholder’s investment at redemption. For example, if you initially invest $10,000, and at redemption the investment has appreciated to $12,000, a back-end sales load calculated in this manner would be based on the value of your initial investment— $10,000—not on the value of the investment at redemption. Similarly, if you initially invest $10,000, and at redemption the investment has declined in value to $8,000, a back-end sales load calculated in this manner would be based on the value of the investment at redemption—$8,000—not on the value of your initial investment in this example. You should read a fund’s prospectus carefully to determine whether the fund calculates its back-end sales load in this manner.

The most common type of back-end sales load is the “contingent deferred sales load,” also referred to as a “CDSC,” or “CDSL.” The amount of this type of load will depend on how long you hold your shares and may gradually decline to zero if you hold your shares long enough. For example, a contingent deferred sales load might be 5% if you hold your shares for less than one year, 4% if you hold your shares for one to two years, and so on until the load goes away completely. The rate at which this fee will decline will be disclosed in the fund’s prospectus.

A fund or class with a contingent deferred sales load typically will also have an annual 12b-1 fee (described below).

Some funds identify themselves as “no-load” funds. As the name implies, a no-load fund does not charge any type of sales load. But no-load does not mean no fees. As described above, not every type of shareholder fee is a “sales load,” and a no-load fund may charge fees that are not sales loads. For example, a no-load fund is permitted to charge purchase fees, redemption fees, exchange fees, and account fees, none of which is considered to be a “sales load.” It is important to know exactly what fees and charges you will be paying, even for no-load funds.

Redemption Fee

A redemption fee is another type of fee that some funds may charge you when you redeem your shares. Typically, a fund expresses the redemption fee as a percentage of the redemption price. Although a fund may deduct a redemption fee from redemption proceeds just like a deferred sales load, a redemption fee is not considered to be a sales load. Unlike a sales load, which is used to pay brokers, a fund typically imposes a redemption fee to defray fund costs associated with a shareholder’s redemption and that fee is paid directly to the fund, not to a broker. The SEC limits redemption fees to 2.00%.

Exchange Fee

An exchange fee is a fee that some funds may impose on you if you exchange (transfer) your shares in one fund for shares of another fund within the same fund group.

Account Fee

An account fee is a separate fee that some funds may impose on you in connection with the maintenance of your accounts. For example, some funds impose an account maintenance fee on accounts valued at less than a certain dollar amount (for example, on accounts valued at less than $10,000).

Purchase Fee

A purchase fee is a type of fee that some funds may charge when you purchase their shares. A purchase fee differs from, and is not considered to be, a front-end sales load because a purchase fee is paid to the fund (not to a broker) and is typically imposed to defray some of the fund’s costs associated with the purchase.

Annual Fund Operating Expenses

In this section, we discuss those items that you will find under the heading of “Annual Fund Operating Expenses” in the fee table.

Management Fees

Management fees are fees that are paid out of fund assets to the fund’s investment adviser (or its affiliates) for managing the fund’s investment portfolio, and administrative fees payable to the investment adviser that are not included in the “Other Expenses” category (discussed below).

Distribution [and/or Service] (12b-1) Fees and 12b-1 Plans

This category identifies so-called “12b-1 fees,” which are fees paid by the fund out of fund assets to cover distribution expenses and sometimes shareholder service expenses. These “12b-1 fees” get their name from the SEC rule that authorizes a fund to pay them. The rule permits a fund to pay distribution fees out of fund assets only if the fund has adopted a plan (12b-1 plan) authorizing their payment.

“Distribution fees” include fees paid for marketing and selling fund shares, such as compensating brokers and others who sell fund shares, and paying for advertising, the printing and mailing of prospectuses to new investors, and the printing and mailing of sales literature. The SEC does not limit the amount of 12b-1 fees that funds may pay. Under FINRA rules, however, 12b-1 fees that are used to pay marketing and distribution expenses (as opposed to shareholder service expenses) cannot exceed 0.75% of a fund’s average net assets per year.

Some 12b-1 plans also authorize and include “shareholder service fees,” which are fees paid to persons to respond to investor inquiries and provide investors with information about their investments. A fund may pay shareholder service fees without adopting a 12b-1 plan. If shareholder service fees are part of a fund’s 12b-1 plan, these fees will be included in the “Shareholder Fees” category of the fee table. If shareholder service fees are paid outside a 12b-1 plan, then they will be included in the “Other Expenses” category, discussed below. FINRA imposes an annual 0.25% cap on shareholder service fees (regardless of whether these fees are authorized as part of a 12b-1 plan).

Other Expenses

Included in this category are expenses not included in the categories “Management Fees” or “Distribution [and/or Service] (12b-1) Fees.” Examples include: certain shareholder service expenses; custodial expenses; legal expenses; accounting expenses; transfer agent expenses; and other administrative expenses.

Total Annual Fund Operating Expenses (or “Fund’s Expense Ratio”)

This line of the fee table represents the total of a fund’s annual fund operating expenses, expressed as a percentage of the fund’s average net assets.

Some funds call themselves “no-expense” or “zero-expense” funds or emphasize their low expense ratios without mentioning other costs investors pay—either directly or indirectly— when investing in the fund.

For example, the fee table in a fund’s prospectus may show no fees for sales or distribution because others, including affiliates of the fund’s investment adviser, may instead be collecting fees for those services. An investor in such a fund may pay these as separate investment fees, such as commissions paid to a broker for the purchase of fund shares or fees paid to an adviser based on a percentage of assets in a wrap fee program.

Also, there may be other costs investors pay indirectly that are not included in the fund’s expense ratio, such as costs associated with the fund’s securities lending activities or transaction costs that the fund pays when it buys and sells its underlying securities.

These additional costs and expenses can reduce the value of your investment.

Related Information

SEC Investor Bulletin: How Fees and Expenses Affect Your Investment Portfolio

SEC Publication: Mutual Funds and ETFs – A Guide for Investors

SEC Investor Bulletin: How to Read a Mutual Fund Shareholder Report

The Office of Investor Education and Advocacy has provided this information as a service to investors. It is neither a legal interpretation nor a statement of SEC policy. If you have questions concerning the meaning or application of a particular law or rule, please consult with an attorney who specializes in securities law.